3. 1934:North Dakota Whips the Big Leagues

5. 1936: Bismarck Runs Out of Gas

1. The Genesis

Baseball history in North Dakota is truly special. Along with Minnesota, North Dakota was one of the few states in the Union where blacks and whites played together without much trouble.

In 1901, Waseca, MN fielded an integrated amateur team that won the State Championship.

In the 1930s, pitcher John Donaldson pitched for Minnesota teams from Bertha to Little Falls and was regarded as the best black pitcher on the road.

In 1930, Little Falls hired Webster "Submarine" McDonald to pitch for their semipro team and he not only turned a mediocre semipro team into a world-beater overnight, he pitched and beat the Minneapolis Millers of the American Association (the top Minor League). The local paper regarded the occasion as the biggest event since Charles Lindbergh (a Little Falls native) returned home after his famous flight.

According to Art Schauer, quoted in the book "Common Ground" by Bruce Berg and Reggie Aligada, the story of Jamestown's historic Jack Brown Stadium, the first black players to play North Dakota semipro ball were Freddy Simms and Chappie Gray. The Hancock brothers, Art and Charlie, followed, the former gaining the nickname "the Black Babe Ruth."

Solomon Otto caught on and off for Dickinson while attending Dickinson State Teachers College and Barney Brown pitched several games for Dickinson.

It was during this time that the rivalry between Jamestown and Bismarck, 100 miles apart, really started heating up. Betting was heavy when the Capital Citians and the Jimmies met, and bragging rights were on the line. Occasionally, one team would hire a ringer from the min

or leagues' Minneapolis Millers or St. Paul Saints of the American Association, hoping to gain the edge. Soon, one or two minor league sluggers wasn't enough. There was a great untapped source of talent in black baseball and the rivalry hit a fevered pitch in 1933...

2. Satchel Arrives

In 1933, Jamestown became the first of the two teams to employ a great black pitcher when they signed Barney Brown, a star left-handed pitcher from the Negro Leagues, who was also a dangerous hitter (in the winter leagues one year he was the top pitcher and hitter). Brown beat Bismarck with relative ease several times and it became clear that Bismarck needed to make the next move in order to compete.

In 1933, the Bismarck town team was put in the hands of car dealership and Prince Hotel owner, Neil O. Churchill. Churchill, who would later become mayor of Bismarck, had been a star player for Bismarck 15 years earlier, and had played against black touring teams several times. To him it was obvious what he needed to do to strengthen his new team: sign black players. Churchill called Abe Saperstein in Chicago whom he had met several times when Saperstein's Harlem Globetrotters had made stops in Bismarck to play a basketball team he sponsored named the Bismarck Phantoms (who actually beat the Globetrotters a few times). It was common knowledge that Saperstein, one of the country's largest bookers of baseball games, was the pipeline to Negro League players.

"I need some good black baseball players," said Churchill.

In a short time a train pulled into Bismarck and out stepped three players: Quincy Trouppe, 20-year-old switch-hitting catcher of the Chicago American Giants; Red Haley, hard-hitting infielder from the Memphis Red Sox; and pitcher Roosevelt Davis of the Pittsburgh Crawfords, one of the top right-handers in black baseball at the time. At last Bismarck had someone to beat Barney Brown–they thought. Unfortunately, Barney Brown continued to beat Bismarck, and Churchill was back on the phone with Saperstein.

"Get me someone who can beat Barney Brown."

"How about Satchel Paige?"

"Will he play in North Dakota?"

"He'll play if the money's right."

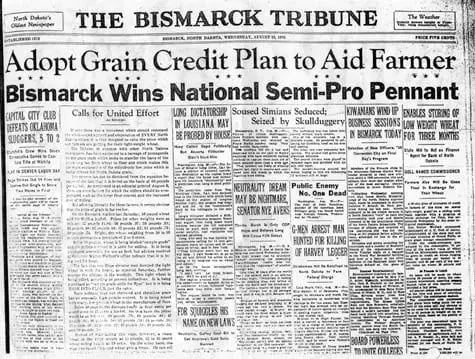

Churchill must have made Paige an offer he couldn't refuse because on August 10, 1933, the Bismarck Tribune made the following announcement: "Satchel Paige, leading right-handed flinger of the National Colored League, will pitch for Bismarck against Jamestown Sunday afternoon."

Gus Greenlee, the Crawfords' owner, got mad at Churchill for "stealing" Satchel away from him and told him over the phone that he was going to "cut him from one end to the other."

Bismarck went "baseball crazy" with the prospect of Paige arriving, and Churchill quickly had extra bleachers built in anticipation of the largest crowd in North Dakota baseball history. Wagers were taken over telegraph wire and Churchill himself bet $1000 with a Jamestown politician.

The day of the game a train brought 1000 Jamestown fans to Bismarck where they were met by the Association of Commerce and taken on a motor tour of the city. Just a few hours before game time Satchel stepped off a train from Chicago and was greeted by several hundred happy Bismarckites. In an interview many years later, Satchel remembered his first game for Bismarck: "It wasn't until after I signed up with Mr. Churchill that I found out I was going to be playing with white boys. For the first time since I'd started playing, I was going to have some of them on my side. It seemed really funny. It looked like they couldn't hold out against me forever after all."

Although it is nearly impossible to believe that Satchel wasn't told by Churchill or Saperstein that Bismarck's team was integrated, it is fairly certain that it was the first "mixed team" he had played with. The big game was everything it was supposed to be, and Paige, despite a 24-hour train ride, left no doubt that he was the best and most entertaining pitcher North Dakota had ever seen. Early in the game Paige delighted fans on a come-backer to the mound when he fielded the ball, bent over, dried his hands on the rosin bag, then fired a bullet to first to get the runner by an eyelash.

Negro League historians have tried for years to discern when Paige first developed his "hesitation pitch"–a pitch in which he would stop mid-delivery for a split second, then continue, shocking the off-balance batter in the process. One thing is certain: Paige was already throwing his hesitation pitch in 1933. The Bismarck Tribune reported that, not only did Satchel acquit himself as the fastest pitcher ever seen in North Dakota, but that he also "used a tricky delayed delivery with great effectiveness." For the game Paige struck out 18 and allowed five "bingles." Barney Brown struck out 13 and also allowed five hits. Neither team scored until the sixth when Jamestown bunched three hits and a walk off Paige and scored two runs. Bismarck breathed easier in the eighth when Haley walked, and Trouppe and Paul Schaefer each tripled to tie the score.

"They get no mo' runs," Paige supposedly told his team on his way to the mound in the ninth. He threw 10 pitches and struck out the side. In the home-half of the ninth, Bismarck's first two batters went down in order before Ralph Sears was hit in the back with a Brown fastball. Bill Morlan followed with a liner into left-field. Jamestown left-fielder, Al Schauer, attempted a diving catch and the ball bounced under his glove and rolled to the fence: the race was on. Sears roared around the bases while Schauer got up, retrieved the ball, and threw a bullet to Jamestown catcher, Charlie Hancock. Sears was waved around third, the ball arrived, Sears slid, Hancock applied the tag, the umpire screamed, "Safe!" and Bismarck went crazy. The crowd mobbed Paige and tore the uniform from his skinny body. North Dakota baseball had officially "arrived."

A rematch was inevitable and a few days later the stage shifted 100 miles east where more than 4000 fans crammed into the tiny Jamestown ball park. Ground rules were necessitated as fans were lined six and seven deep around the entire field. Bismarck scored in the first when Trouppe drove in Haley with a double; Jamestown tied the score in the fourth when Art Hancock drove one of Paige's 100 mile-an-hour bullets over the crowd in right. Paige and Brown settled down and traded strikeouts until the game was called by darkness after 12 innings. Paige ended with 18 whiffs, Brown 11.

The crowd cried for more and Churchill challenged Jamestown to a three-game series in Bismarck to crown the state champions. Bismarck had two weeks before the big series and Churchill took advantage of having the rubber-armed ace and pitched Paige every chance he got. Against Beulah, North Dakota, Paige struck out 20 and granted three hits in an 8-0 victory. A few days later Hack Wilson and the Sioux City Stockyards, one of the country's strongest semipro teams, came to Bismarck and were slaughtered, 9-2; Paige k'd 13.

The Bismarck-Jamestown series finally came, and again special ground rules were necessitated by the huge crowd at the Bismarck ballpark. Fans without tickets lined up on an elevated train track beyond right-field, much like the apartment-roof dwellers outside Wrigley Field in Chicago.

The first game pitted Barney Brown against Paul Schaefer and ended in a seven-all tie, despite three home runs by Jamestown's Art Hancock.

Sunday was the big one: Foster versus Paige. Foster was impressive but wild with 10 k's, 10 walks, and six hits allowed. Paige struck out 15, walked four and won the game with a dramatic ninth inning single, after which he was mobbed for 4000 fans.

The anti-climatic finale was won by Bismarck's Roosevelt Davis and Bismarck's boys were the indisputable North Dakota state champions!

Word came from Chicago that Willie Foster and Satchel Paige were named to oppose each other in the first East-West (Negro League All-Star) Game and Foster left for the Windy City (the first major-league All-Star game was also played in Chicago in '33).

The American Association All-Stars, according to the Bismarck Tribune, were going to be a great challenge to Paige. After all, the All-Stars weren't another semipro team. They were the best players from the highest level of the minor-leagues, just a step below the major-leagues.

Challenge? Bismarck borrowed Barney Brown from Jamestown and slugger Beef Ringhofer from the All-Nations. Brown homered, Ringhofer collected five hits, Trouppe three, and Paige two, as Bismarck won, 15-2. The only two All-Star runs came courtesy of Paige's clowning in the last inning. A pop fly to the mound by St. Paul Saint Angelo Giuliani fell when Paige tried to catch it one-handed. The next batter hit a perfect double play ball back to the mound which Paige fired into center. The next batter tripled in both runs with one of his team's four hits of the day.

In his short stay in Bismarck, Paige pitched in nine games with seven wins, no losses, and averaged nearly 15 strikeouts per game. More importantly to Churchill, he packed the house every time he pitched. As businessman Churchill looked back on the last month of the season, he must have seen the great financial possibilities of fielding a classy ball club in the pastures of North Dakota: 4000 fans at 40 cents a head, plus beer and peanuts! It was only the beginning.

3. 1934: North Dakota Whips the Big Leagues

As the snow began to melt in the spring of 1934, Churchill was busy readying Bismarck for another big season. With personal and city funds, along with federal emergency relief labor, he launched a $5000 improvement plan on the Bismarck ball park, providing for 3000 seats in a new grandstand, a bleacher section for children, and room for 500 cars to park and watch the game along the outfield fence. It was, without question, the finest baseball facility in the Midwest and, according to Churchill, larger than every major-league park except Philadelphia's Shibe Park–332 down each line and 460 to center.

Why not have a first-class ballpark? With Satchel Paige coming back, the park would be constantly packed and would pay for itself in a short time.

As it turned out Paige was a no-show. In fact, all year long Churchill waited for Paige, who had promised to play for Bismarck. "Plan B" for Churchill was signing young fireballer Sug Cornelius of the Chicago American Giants. The pitcher was ready to hop a train to Bismarck when American Giants' manager, Dave Malarcher, caught wind of his plan, and had him thrown in jail for attempting to jump his contract. Churchill couldn't have been too upset, though, because Bismarck was still loaded. They had Red Haley and Quincy Trouppe back, along with local favorites Harold Massman, Bill Morlan and Mike Goetz. Churchill signed quality pitchers Lefty Vincent and Spoon Carter from the Negro Leagues and Joe Desiderato, Beef Ringhofer and Mike Canizzo from the All-Nations to play third, first and outfield respectively.

On the wave of Bismarck's 1933 season, several North Dakota towns jumped on the bandwagon and began signing top talent from Organized Baseball and the Negro Leagues. Valley City signed brothers Art and Charlie Hancock, two black semipro veterans, and player-manager George "Showboat" Fisher, a lifetime .335 major-league hitter from the St. Louis Cardinals.

New Rockford signed catcher Jest Rhodes of the Kansas City Monarchs and outbid Bismarck for Roosevelt Davis.

Jamestown, with backing from the Gladstone Hotel, built the strongest North Dakota team to date signing "the colored quartet" of Barney Brown, Bill Perkins, Steel Arm Davis and Double Duty – Duty being made player-manager.

Jamestown further strengthened their team when they signed former Minneapolis Miller Dan Oberholzer, once described by legendary Miller manager, Mike Kelley, as "a corking third baseman with a rifle-like arm and great speed on the bases."

In Jamestown's first game, Double Duty tossed a shutout beating Roosevelt Davis and New Rockford and began a five-month period during which Jamestown dominated semipro baseball in North Dakota.

During a game in May this was illustrated when the Twin Cities Colored Giants came to town. The Colored Giants, led by slugger Maceo Breedlove and Negro League hurler "Wild Bill" Freeman, were the best Minneapolis and St. Paul had to offer. They were the strongest of the traveling clubs from the Twin Cities and spent much of their time beating up on Northern League (Class D minor-league) and Southern Minny League (white semipro league) teams.

Jamestown embarrassed the Giants in a seven-inning game, shortened not by darkness, but by the visitor's request. Double Duty allowed seven hits (one to Breedlove) and struck out 10 while Freeman was being battered about. Perkins, Davis, Radcliffe and Brown--referred to as the "colored quartet" by the Jamestown Sun--each collected two hits in the fifth inning and Double Duty finished with five hits for the day. Perkins needed a single in his last turn at bat to hit for the cycle but lined one in the gap and couldn't help but take second. Final score: 19-3.

A week later Double Duty won both games of a doubleheader against the black Detroit Giants, allowing six hits in each. In June, Jamestown beat the House of David and their only beardless player, Babe Didrickson, and later in the month whipped the odd pitching combination of Hall of Famer Grover Cleveland Alexander and Elmer Dean, the lesser known brother of Dizzy and Daffy.

The House of David was one of the most popular semipro teams on the road. The Davids, based out of a religious commune in Benton Harbor, Michigan, all wore long beards (except for Didrickson) and supposedly swore off meat, smoking and sex. The fact is, the original teams from the religious sect did probably follow these rules, but as time went by the beard was all that was required if you could play ball. It's reported that Shoeless Joe Jackson grew a beard and played with the House of David after being shunned by Organized baseball. There were several David players of Major League ability and a few actually left the team and went immediately to the Big Leagues.

Radcliffe completely dominated the House of David during the 1934 season despite one of its strongest teams ever--virtually the same team that in 1933 defeated the St. Louis Cardinals, St. Paul Saints (American Association), Rochester Red Wings (International League), Harrisburg Senators (New York-Penn League) and Oakland Oaks (Pacific Coast League).

In one game against the "Bearded Beauties" Radcliffe was dubbed "Triple Duty" after he went three-for-three at the plate, made a diving catch while playing right field, threw out a pair of runners while catching, and struck out two batters in one inning of work on the mound. In another game against the Beards, Duty struck out 18.

In the hitting department Double Duty had several memorable games. Against Valley City he homered off both Jonas Gaines and Spoon Carter, and a few weeks later beat Gaines again with an opposite-field grand slam homer into the James River.

In September Bismarck and Jamestown combined forces and swept a five-game series against the Chicago American Giants with Double Duty leading the way. The Giants, Negro National League champions in 1933 and 1934, featured Larry Brown, Mule Suttles, Jack Marshall, Alec Radcliffe, Hurley McNair, Willie Wells, Willie Powell, Sug Cornelius and Johnny Hines.

In mid-September it was announced that a Major League All-Star team was going to make a stop in the Dakotas before going overseas for a series in Japan.

Babe Ruth was announced to be leading the stars but at the last minute was replaced by Jimmie Foxx. Unfortunately, the baseball world was robbed of seeing two of baseball's biggest personalities go head to head. (Ruth did make the trip to Japan, just not to the Dakotas).

The All-Star team, managed by Connie Mack's son, Earle, was a great one with Foxx (.334, 44 homers and 130 RBIs in 1934), Heinie Manush (.349, 42 doubles, 89 RBIs), Roger "Doc" Cramer (.311, 202 hits), Pinky Higgins (.330, 37 doubles) and pitchers Rube Walberg (6 wins, 7 losses), Monte Weaver (11-15), Ted Lyons (11-13), and Earl Whitehill (14-11) .

North Dakota combined the Bismarck, Jamestown, and Valley City teams to face the big-leaguers but were weakened when Desiderato had to return to Chicago and Trouppe left for his home in St. Louis. Double Duty was also missing for the first game when he returned briefly to his home in Chicago. Luckily the pitching was bolstered when Chet Brewer of the Kansas City Monarchs was added to the team.

The Big-Leaguers arrived in Valley City for the first game and the North Dakota semipros jumped on White Sox' hurler Lyons for 11 hits and six runs in five innings and won, 6-5. Foxx, who started in professional baseball as a pitcher, hurled the last three innings for the big-leaguers and struck out six without allowing a run. Barney Brown pitched well and got the win, despite giving up homers to Cramer and Red Kress.

The two teams moved on to Jamestown and Brewer completely dominated the big-leaguers, shutting them out on four hits with six strikeouts--Manush three times. Double Duty, back from Chicago, singled twice, Steel Arm Davis belted a double and two homers, and Art Hancock added a double and two singles.

The following day at Bismarck, Duty matched up against the Washington Senator's Whitehill and North Dakota exploded for three runs in the first two innings, added four in the fifth, and four in the eighth to win, 11-3. Double Duty led the offense with a double and two singles, followed by Hancock who tripled and homered. The Big Leaguers' only runs came in the ninth inning when Duty walked two batters ahead of a Pinky Higgins home run. In all, Duty allowed eight hits and struck out three. After the blowout one Major Leaguer was reported to have remarked, "I knew there were a lot of good colored players. I just didn't know they were all in Bismarck!"

The Red Sox won 38 of 53 games, had a winning record against every team they played, and attracted more fans per game than every Minor League team in the country. Double Duty finished with 17 wins, three losses, three saves, and allowed only 17 walks all season! Over nine innings he averaged more than nine strikeouts, one walk, eight hits, and less than two-and-a-half earned runs. Nine times during the season he struck out ten or more batters and his high total for bases on balls in a game was two. He pitched against Bismarck twice, winning both and had a perfect record against the Kansas City Monarchs and Chicago American Giants--probably the two strongest Negro League teams on the road.

Without a doubt, at this point in his career, Duty was one of baseball's best pitchers. Barney Brown was also impressive with a 14 win, six loss record and Lefty Thompson finished six and four. As for hitting, Cy Perkins led the regulars with a .422 average and 16 home runs in 154 at bats (57 home runs per 550 at bats). Duty followed hitting .355 with seven homers (21 home runs per 550 at bats), and "Steel Arm" batted .324 with 18 homers (53 home runs per 550 at bat). Danny Oberholzer (.317 and three homers in 123 at bats) and Barney Brown (.308, two home runs in 123 at bats) were the other regulars over .300.

Bismarck finished 61 and 18, with Quincy Trouppe, Joe Desiderato, Beef Ringhofer, Mike Cannizo and Harold Massman leading the offense. Barney Morris pitched well for the Capital city, and got plenty of help from Negro Leaguer Lefty Vincent.

Could North Dakota baseball get any better?

4. 1935: National Champs

"It was in Bismarck, N.D. There was a white man out there named Neil Churchill who liked baseball. He was an auto distributor and he wanted a ball team for Bismarck. He was fulla ambition for baseball for his town. He's been mayor ever since and I guess someday he'll be Governor of North Dakota. He gave me three autos.

"

In [1935] Churchill got a team together and that's my team of all-stars. Never was such a team. Man, couldn't beat that team. Hit and field and, boy, did we have the pitchers. We was a mixed team, colored and white.

"

We won the first Wichita semi-pro tournament and they barred us from playing. No mixed teams. Why, we was just too good, that's all. But nobody paid no attention to us when we went into that National tournament, be did we wallop 'em all. Nobody could touch us. And boy did them Bismarck people like us. Those farmers that were our fans came to town with hats full of money to bet on us.

"That was the best team I ever saw; the best players I ever played with. But who ever heard of them?"

--Satchel Paige, from the Chicago Daily News, 6/18/43

Ballplayers spin yarns--that's what they do best--and Satchel Paige had some doozies about the '35 Bismarck team. He claimed in a magazine interview in the 1950s that the team ended with 100 wins, only one loss, and that the one defeat came against Jamestown when he accidentally motioned for his fielders to sit down while he struck out the side--according to the story, an easy fly ball turned into a game-winning homer. Interesting? Yes. True? No.

In fact, Bismarck lost 22 games on the year and Satchel lost the very first game of the season against Jamestown (now an all-white club) when he was outpitched by former House of David pitcher, Ed Brady. Satchel didn't need to tell tales when the Bismarck team was concerned, though, because the facts were impressive enough.

The '35 Bismarck team was a peek at what integration could be. Churchill signed the best talent available, period, regardless of color. It paid off. The top five starters in the pitching staff combined for 55 wins and six losses and the offense outscored their opponents by nearly 300 runs.

There are bargains and there are BARGAINS and Churchill negotiated the latter when he picked up two of the Negro League's greatest pitchers early in the season. BARGAIN number one came in signing Barney Morris, a hard throwing knuckleballer, for $175 a month. Morris led Churchill to BARGAIN number two when the Negro Southern League's Monroe Monarchs came to Bismarck. Morris, an ex-Monarch, gave glowing reports of a young pitcher with loads of talent--Hilton Smith. After the doubleheader, Churchill approached Smith and offered him a contract with Bismarck at a considerable raise (probably to around $150 a month). The Monarchs drove off and Smith stayed.

The next big move came when Churchill signed Vernon "Moose" Johnson. Moose had spent most of 1934 with the Sioux City Cowboys of the Western League whose home field, Stockyard Park, was probably the largest ball park in minor-league or major-league history. Are you ready for this? The left field foul pole was 450 feet from home plate and the center field fence was an unbelievable 675 feet from home. The right field line was only 307 feet from home but angled sharply to center--the right field gap being more than a 500-foot clout away. Despite the large dimensions, Moose finished fifth in batting at .340 and led the league in homers with 24 in only 62 games-- a pace to hit 60 homers in a 154-game season! Moose's problem was never hitting or fielding, but drinking. During the '34 season with Sioux City, Moose was suspended and fined for "breaking training rules" and the day he returned he won a game against Rock Island with an 11-inning, 450-foot homer. In '33 Moose had led the Western League in hitting with a .381 average for the Muskogee Orphans but didn't have enough at bats to qualify for the batting title due to several suspensions. Moose continued the trend with Bismarck.

Moose arrived in Bismarck and despite playing with sluggers Trouppe, Haley, Radcliffe and Desiderato, established himself as the best hitter many had ever seen--even giving Josh Gibson a run for his money when he wasn't seeing double! In mid-June Moose went on an awesome home run tear that left opposing players in awe. On June 16th Moose homered against the Kansas City Monarchs, on the 18th against the House of David, and on the 24th against Jamestown. He missed a pair of games due to "stomach troubles" and his first day back against the Colored House of David he homered twice.

In June Bismarck released batting averages for the team and Moose was leading the pack with a .469 average followed by Trouppe (.392), Haley (.333) and Desiderato (.328). A good indication of the pitching Bismarck faced lies in the fact that Charlie Bates, a slugger from the Western League, was dropped from the team due to light hitting. Bates had led the Western League in hits in 1934 for St. Joseph but couldn't hit a home run in over 60 at bats for Bismarck. Part of the difficulty came because semipro umpires rarely stopped pitchers from throwing spitballs, emeryballs and beanballs. Is it a wonder Double Duty flourished?

Speaking of Double Duty, his first Bismarck mound appearance of 1935 was a gem against Jamestown when he fired a one-hitter to beat former Major Leaguer "Iron Man" Ray Starr (according to The Ballplayers by Mike Shatzkin, Starr got his nickname by pitching more than 40 doubleheaders in the minor-leagues).

The final piece of the puzzle was put in place when Danny Oberholzer returned to North Dakota to play second base, giving Bismarck an infield of Desiderato, Axel Leary, Oberholzer and Red Haley around the horn.

Once the pitching staff was set with Paige, Morris, Duty, and Smith, Bismarck won 28 out of 29 games--the one loss coming when Smith lost to Devils Lake, a Cleveland Indians' farm club, 5-4. Buck O'Neil, All-Star first baseman and teammate of Satchel's with the Monarchs, once remarked that he "knew for a fact" that Satchel pitched in 30 straight days for Bismarck in 1935. Satchel probably pitched in even more. During a stretch in July, Bismarck played 32 games in 27 days and Satchel pitched in every one. Paige's usual routine called for him to pitch a complete game every fourth or fifth contest (he never failed to complete a game he started all season), and one or two innings of work in the others as he was advertised to pitch every road game. Despite the hectic schedule, Paige was practically unhittable.

Newspapers in South Dakota and Canada reported several times that the Bismarck fielders started to walk to the dugout while Paige mowed down the last man.

According to one newspaper report, "Double Duty was another the fans went for." Behind the plate Duty chattered constantly, asked batters why they were insulting Satchel by bringing a bat to the plate, and bet runners a dollar if they could steal on him. In one game Duty played right field and when a base hit came to him, he put on an act, frantically searching for the ball, all the while looking out of the corner of his eye at the runner, waiting for him to try for the extra base. When the runner didn't try to advance Duty calmly picked up the ball, flipped it in, and let out a laugh. The crowd roared.

Great teams need an event to show off their talent and as fate would have it the first National Semipro Championship tournament was organized in Wichita, Kansas in 1935. The brains behind the event was a cigar-chomping promoter-salesman-newspaperman named Raymond "Hap" Dumont. Dumont dreamed of organizing the greatest semipro baseball tournament the country had ever seen and was so sure that it would be a success that he convinced Wichita to build Lawrence Stadium in which to hold it.

Starting in 1922 the Denver Post newspaper had sponsored a semipro tournament but most of its teams came from Colorado and the surrounding states, with only a handful of top-notch teams. Dumont, on the other hand, wanted every team in his tournament to be loaded. He spent 1934 and 1935 scouring the country for the best semipro teams in the country and Bismarck was one of the first to receive an invitation. Churchill RSVP'd with his acceptance and scheduled plenty of games the last month of the season to get his team into top form.

Following are a few memorable games:

June 21: In Winnipeg Morris threw a three-hitter and struck out 12 against the Negro Southern League's Shreveport Acme Giants, starring youngsters Howard Easterling and Johnny Markham. Desiderato and Morris both bounced homers off an Amphitheater's roof beyond the center field fence.

July 7-8: Barney Morris almost single-handedly won a Canadian tournament for Bismarck when he pitched three complete games in two days and won by scores of 7-2, 9-0, and 9-1.

July 12: The Mexican LaJunta Charros came to town with a record of 46 wins, two losses, and victories over the Fort Worth Cats and San Antonio Missions of the Texas League. Frank "Happy" McKeown, "the world's greatest cheer-up man," entertained the crowd by showing how he could throw, catch, and bat a ball despite the loss of both arms. The Charros then got throttled, 8-1, with Paige pitching and "Big Moose" homering twice.

July 31: The summer heated up and so did the Jamestown-Bismarck rivalry. The Red Sox were frustrated all afternoon with Hilton Smith tossing a three-hitter and Double Duty tossing out a pair of runners attempting to steal. In the sixth inning Moose Johnson smacked Bismarck's fourth double of the game (Red Haley had the other three) which brought up Double Duty. The Jamestown pitcher, Schmidt, nailed Double Duty in the head and both benches cleared. It took 15 minutes before order was restored and on the first pitch after play resumed, Hilton Smith hit an apparent home run. Jamestown argued that the ball bounced over the fence and when the umpire didn't agree another scuffle erupted. Trouppe, a champion amateur boxer, had to be restrained from clobbering someone and Jamestown quit and went home.

August 3-4: Bismarck swept a three-game series with the Minnesota state semipro champions from St. Cloud. In the first game Desiderato ripped three hits and tossed a seven-hitter. In the second game Radcliffe and Trouppe each performed double duty when they both caught and pitched half the game, each threw out a runner trying to steal, gave up four hits each, and each collected a base hit. The finale was a blowout, 8-1.

August 9-11: The weekend before the Wichita Tournament began, Bismarck went through their final tune-up against the Twin City Colored Giants. Double Duty was given the series off to rest for the tournament and Trouppe sat on the bench with a minor injury. It didn't matter. On Friday Morris won, 8-5, with Leary homering twice, Oberholzer and Smith once.

On Saturday Smith won, 9-5, with new signee Art Hancock, homering once and Moose connecting twice.

Sunday's game was a massacre and Paige, who didn't want to get rusty, pitched a complete game only four days from the start of the National Tournament. The Bismarck Tribune creatively reported the game:

"Five First Inning Home Runs Feature Weird Game Sunday; Paige Calls in Fielders and Finishes Last Inning With Morris Catching With an overture of five home runs in the first inning, [by Oberholzer, Desiderato, Hancock, Smith and Johnson] opening a riotous grand opera of extra-base hits and a profusion of singles, Bismarck's mightiest baseball team sang its swan song for the season to home fans Sunday afternoon by crushing the Twin City Colored Giants, 21 to 6. Sunday's game had both pathos and bathos. To quell the staccato-like explosions emanating from Bismarck's bludgeons, which were becoming monotonous as the game wore along, the local batsmen in their last inning batted from the opposite side of the plate to which they are accustomed."

In the ninth inning Satchel called in his fielders, struck out the first two batters, and up stepped Maceo Breedlove. In the previous two games, Breedlove had collected two hits off Morris, and a homer and single off Smith. Against Paige he already had two doubles and a homer and was looking for more. Breedlove remembered "the greatest moment in my life" over 50 years later: "With two outs in the ninth inning Satchel was gonna strike me out to end the game. Satchel waved all the players off the field except his first baseman, Red Haley. Satchel had four or five black guys on the team and they knew about me. One of them said, 'They done picked out the baddest boy on that ball club to fool around with!' " And looked like everybody in North Dakota at that ball game. At that time Satchel Paige was the greatest man that was out there--he struck out a man any time he want to. So they had us beat pretty bad. They was about six or seven runs ahead of us. So all the fielders came in--wasn't nobody out there but him and the first baseman. Now he gonna strike me out!

"Satchel was throwing them fastballs and I kept fouling them off. I bet I hit about 15 foul balls off him. See, he was throwing that ball so fast I couldn't get around in time and I fouled it off. So finally he threw me his dinky curveball up there and I straightened it out into left field--nobody out there to get it and I went around the bases and came back in.

"I had one boy playing on my club and after he found out Satchel was gonna pitch he went out sick that day--he didn't want to play against him. He said to me, 'Why didn't you let Satchel strike you out, too?' I told him, 'I wouldn't let nobody make a fool out of me in front of all these people if I can help it!'"

Meanwhile, in Wichita, Honus Wagner was named guest of honor of the upcoming tournament and was put on a committee with Ty Cobb and Walter Johnson to solve any disputes that might arise. Joe E. Brown wired that he would be present at the games. The field was shaping up nicely. The Baby Ruth's, sponsored by the Curtis Candy Company, were chosen from 1500 semipro teams in greater Chicago and the Union Circulators were chosen as the best from New York City with ex-professionals at every position. An All-Indian team from Oklahoma was invited as was a Japanese team from Stockton, California managed by Cincinnati Reds scout Jack O'Keefe and featuring 59-inch tall pitching ace, Kenso Nushida, formerly a star with the Sacramento Salons of the Pacific Coast League.

The Monroe Monarchs, San Angelo Colored Sheepherders, Memphis Red Sox and Denver White Elephants (with Buck O'Neil and Oliver Marcelle) were chosen from black traveling clubs and the tournament was billed both as the "All-Nations Tournament" and the "Little World Series."

The oddest entry was the Stanzaks team from Waukegan, Illinois. The team consisted of former Milwaukee Brewers third baseman Frank Stanzak and his nine brothers: John, Joe, Bill, Mike, Edward, Bruno, Louis, Martin and Julius. They were chosen as "brother champs" after beating the Marlatts of Wyoming and the Siblilskis of Pennsylvania. The Stanzaks actually won two games and nearly pulled off the upset of the tournament when they came up a run short against Denver United Fuel, backed by a million dollar oil refinery.

Many teams would arrive in Wichita in expensive tour buses with their team name painted on the side, backed by million dollar factories. Bismarck, on the other hand, piled in two cars--a Chrysler Airflow and Plymouth--and roared off to Wichita.

On the way they stopped in Kansas City to pick up more pitching help in old friend Chet Brewer, giving Bismarck probably the greatest pitching staff in baseball history. 60 miles from Wichita the team stopped for food and fuel in McPherson, Kansas and were promptly talked into a game with the Dickey Oilers, also entered in the tournament.

The McPherson Daily Republic: "SATCHEL STAGES A SHOW--McPherson baseball fans saw some real baseball yesterday afternoon. The Bismarck team defeated the Dickey Oilers by a 14 to 0 count, doing some heavy hitting when hits meant runs. The big feature of the game however, and one that was worth more than the admission price, was the show staged by the one and only Satchel Paige, colored pitcher, rated by many experts as the greatest twirler, white or black, in the country.

"Satchel hadn't been used and the fans were yelling for him to take the mound. In the final inning he accommodated the spectators. He walked to the mound after waving his outfielders to stay on the bench. He struck out Ferguson and Butler, each on three pitched balls. Then the first baseman walked to the center of the diamond, leaving a hole on the right side of the infield. Weber, next Dickey batter up, rapped out a line drive through this hole that went for three bases before the ball was retrieved. Nothing daunted Paige as he then sent his infielders to the bench and with nobody but his catcher for company he pitched to Britt who rapped one down the center of the field, Satchel got it off the ground and then ran Britt down and tagged him before he got to first for the third out. It was a 'stunt' that the fans enjoyed."

August 14, 1935 was the day of Bismarck's opening game. With sports bars yet to be invented, Bismarck fans instead crammed into the lobby of the Prince Hotel and watched a telegraph spit out accounts of the big game. Bismarck was in trouble right off the bat when Desiderato uncharacteristically threw a ball away and two unearned runs scored without a hit (Paige listed Desiderato on his all-time All-Star team at third base with Negro Leaguer Judy Johnson). Paige then fell into a groove and started popping Duty's catcher's glove like a series of gunshots.

Julius Stanzak of the Stanzak Brothers: "Paige was incredible. All I can remember is the catcher, Radcliffe, having to put a piece of steak in his glove so Paige wouldn't take his whole hand off."

Bismarck trailed, 3-2, in the seventh when they rallied for four runs capped by Trouppe's two-run double and Paige cruised to a 6-4 win. Duty went hitless but reached on an error, stole a base, and scored. He would hit safely in the remaining six games.

Satchel, working on one day's rest, ended with 17 k's and left writer Roy Octavus Cohen inspired: "Folkses, youall lookin' at de best pitchah in de world. Yassah, dats him, ole Satchel Paige. You boys don't need to be discouraged--he mows de best of de big leaguers down just the same as he's a-mowing youall. Youall should have seen old Satchel out in the Los Angeles winter league. Yassah. Carl Hubbel and old Diz Dean just couldn't hold a candle to that boy out there. He won 17 games. Yassah. 17. And how many did he lose? Is you askin' me? Listen, folks, ole Satchel didn't lose none. That's the kind of pitchah youall is lookin' at. The best pitchah in de world!"

In the second game Duty singled and doubled to lead the offense with Moose and Hancock also collecting two hits each. But guess who grabbed the headlines again? Ole Satchel.

Double Duty: "It was so hot that day I had to put a wet towel on my neck between innings. Chet Brewer pitched for us and he started getting tired from the heat--it was about 109 degrees. He was getting in trouble and I told Satchel to warm up.

"In the sixth inning we was leading by one run and they had three men on base. Brewer had walked the bases loaded 'cause the umpire was squeezing us. I looked down in the bullpen and Satchel was down there playing pepper with three little white boys--hadn't thrown the ball yet. So I told him to come on.

"He came up there and he hadn't thrown a pitch yet. Back then you got 10 warm up pitches. He threw his 10 pitches and all he did was struck out the side on nine pitches. Oh, he threw that day. God bless him. Satchel finished the game and didn't give up a hit--he struck out seven of the eight batters he faced. They pitched a boy named Chambers who went up to the Big Leagues but he couldn't handle the heat and we got him. Me and Quincy had big days at the bat. I had a double and a single and drove in three runs. Quincy hit a home run off the train going by in the outfield--you could hear it hit. BOOM! We won, 8-4. Trouppe and I really tore that ball up in that tournament!"

Before game three, Wichita Water pitcher Maxie Thomas, who had pitched against Oberholzer and Moose in the Western League, boldly predicted, "Give me two runs and I'll guarantee a victory." Wichita scored one, Satchel drove in two, Bismarck won, 4-1. Sorry, Maxie.

The fourth game came against Shelby, North Carolina and Chet Brewer fired a two-hitter. Oberholzer, Radcliffe, and Desiderato each belted two hits in a 7-1 win.

Bismarck's next opponents were the Halliburton Cementers from Duncan, Oklahoma. Through the first few rounds, the Cementers had been the hardest-hitting squad in the tournament, averaging nearly 13 runs per game. Churchill had hoped to start Barney Morris in one of the games but decided to play it safe and sent Satchel back to the mound for the fifth time in eight days. When the dust cleared and Duty's hand stopped throbbing, the Cementers had five hits and one run; Paige had 16 strikeouts. Haley led the hitters with two singles and a double. Duty doubled to start a second inning, two-run rally. Plenty.

Bismarck's sixth opponents, the Omaha V-8's, made it to the sixth round by beating the Memphis Red Sox in a game marred by a brawl that saw five thousand fans storm the field. One Omaha outfielder was hurt in the melee--Johnny Rosenblatt, namesake of Rosenblatt Stadium, home of the College World Series. Brewer pitched a good game and got loads of support from his battery-mate. In the sixth inning, with the bases loaded, an Omaha batter hit a chopper in front of the plate. Double Duty, seeing that Brewer was slow off the mound, pounced on the ball, then dove for the plate to get the force-out a split-second before the runner from third scored. The next batter hit a ball back to the mound which Brewer bobbled and then whipped home for the force. The ball was in the dirt but Duty scooped it out, along with a glove full of sand, to end the inning. Offensively Johnson furnished the highlight by hitting the farthest home run of the tournament and Bismarck won, 15-6. Six up, six down, and the final game wasn't for two more days, giving Paige a season-high three days rest between starts.

In the final game the opponent was again the Cementers of Duncan, Oklahoma who had come through the loser's bracket. Duncan had a rested Augie Johns, formerly of the Detroit Tigers, ex-Boston Brave John Paul Jones in the bullpen, and the top hitter in the tourney in Joe Hassler, also a Major League veteran, who would remark after the game, "I never faced a pitcher as fast as [Satchel Paige]. I think only Lefty Grove in his prime could come up to Paige in sheer speed."

A wrench was temporarily thrown into the works for Bismarck when a certain outfielder didn't show up at the ball park for the big game.

Joe Desiderato: "We won the first six games of the tournament and we had one more game to play. Moose was on the wagon and all of a sudden he never showed up and I'll be a son of a gun if he didn't come to the ball game or nothing. We found him the next day--he was laying out in the street some damn place. He really had it in him."

Hancock was moved from right to left, Hilton Smith batted cleanup. Duncan scored in the first and Smith singled in Trouppe to tie the score in the bottom half. The crowd of over 10,000 had to be moved back as they kept creeping closer and closer to field. For the next five innings Paige and Johns were nearly untouchable.

The Cementers had a chance to score in the fourth when their speedy left fielder beat out an infield hit and stole second. He tested Duty's arm one more time and was shot down trying to steal third.

Double Duty: "We were never worried because we knew Johns would crack before Satchel. Satchel could throw that ball so goddamn hard it looked like it disappeared. I never will forget what Berney Neis from the Brooklyn Dodgers said when we played that final game. We were playing the final game for the money on a Friday night.

"In the 6th or 7th inning Berney Neis came up to me when I was on the on-deck circle. He said, 'Double Duty, I'm glad to see you'all win it if we can't. But it's a damn shame!' I said, 'What do you mean?' He said, 'To pitch that man under these lights when you can't see him in the day!' I said, "'Well, I don't know what he's throwing. I'm just holding my mitt up.' Oooh! Satchel was overbearing! It was 1-1 in the seventh and Oberholzer was on third. Red Haley doubled to center, Trouppe came up and hit one off the center field fence--almost put a whole in it--Wham! Art Hancock singled, I doubled, we got three runs. So Satchel was down in the dugout drinking Coca-Cola. He leaned over to me--he used to call me 'Homey'--he said, 'Homey, there's work to be done. I'm gonna show these sons of--I'm not gonna say the name--that it ain't their night out here.'

"And I never will forget this as long as I live. In the last inning we had them, 5-2, the money on the line--he threw nine pitches. BOOM! BOOM! BOOM! The last batter struck out and the umpire said, 'Boy, you should'a swung 'cause you outta here!' "George Raft was at the game. I was at the hotel getting our money and he said, 'Double Duty, you thought you were gonna suck us in. We knew you were gonna win. We didn't bet.'"

Quincy Trouppe: "After the game was over, Hilton Smith and I went to turn in our uniforms and pick up our checks. As we entered the hotel lobby the tournament organizer, Mr. Dumont, called us aside. 'Boys, I was talking to a couple of scouts yesterday at the ballpark. What do you suppose one of them said to me? This one scout said he would recommend paying each of you boys $100,000 to play ball if you were white.' 'Well, Sir,' I said, 'We're available right now. I'm sure you've noticed that color doesn't mean a thing on our ball club.' 'Sorry, fellows,' he said, 'I just thought you might like to know what the scouts think of you as ballplayers.'"

Paige was named Most Valuable Player and "Outstanding Pitcher" in the tournament and his 60 strikeouts are still a tournament record at the writing of this book despite some great pitchers competing in Wichita over the years: Allie Reynolds, Rex Barney, Van Lingle Mungo, Harvey Haddix, Blue Moon Odom, Tom Seaver, Don Sutton, Ron Guidry, Steve Howe, Rick Aguilera, Roger Clemens and Greg Swindell to name a few.

At season's end it could be argued that Moose Johnson had one of the greatest offensive seasons by a hitter in any league. He led the team in average and belted 25 homers in 192 at bats. In comparison, Quincy Trouppe, one of the most powerful hitters in Negro League history, homered eight times in one less at bat.

The rest of the team didn't do too badly either. Five regulars besides Moose batted above .300--Double Duty, Dan Oberholzer, Axel Leary, Hilton Smith and Quincy Trouppe.

The story of the season, though, was the greatest pitching staff in baseball history. The "Big 5" of Satchel Paige, Double Duty, Hilton Smith, Barney Morris and Chet Brewer combined for a .902 winning percentage with 13 shutouts. Neither Duty nor Brewer lost a game and Smith lost once. These five aces would all pitch in East-West All-Star games and all but Brewer won at least one East-West game.

Barney Morris, "the weak link," posted a 12-3 record, with his losses coming on scores of 2-1, 3-0 and 9-4. He had been, and would continue to be, the ace of most teams he played for.

What did Paige do? 30 wins, two losses (by scores of 2-1 and 4-3), 330 2/3 innings in 48 appearances. Accounts of three away games were not published anywhere, but odds are that Satchel pitched in all three, meaning that he pitched in half of Bismarck's games!

On the financial side, all home games were packed to capacity and for the season Bismarck drew more than three times as many fans as the St. Louis Browns of the American League! According to Lost Ball Parks by Lawrence S. Ritter, the Browns could only entice 80,922 to watch their terrible brand of baseball in 1935 (1,051 per game), while Bismarck drew more than 175,000 to 50 home games (3,500 per game).

Was Satchel right? Was it the greatest team of all-time?

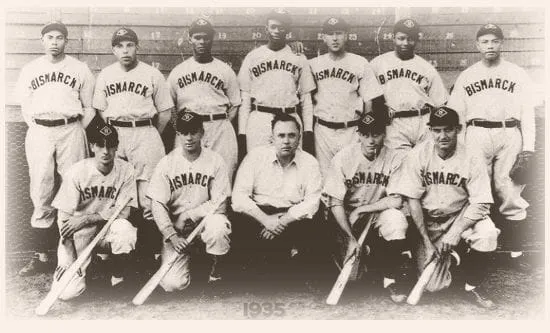

Front row, l-r: Joe Desiderato, Axel Leary, Neil Churchill, Danny Oberholzer, Ed Hendee.

Back row, l-r: Hilton Smith, Red Haley, Barney Morris, Satchel Paige, Moose Johnson, Quincy Trouppe, Double Duty Radcliffe.

5. 1936: Bismarck Runs Out of Gas

The baseball season of 1936 in North Dakota was bitter-sweet. After the climax of the year before, Satchel Paige had returned to the Negro Leagues with the Pittsburgh Crawfords, Double Duty was hired as player-manager of the Claybrook (Arkansas) Tigers, Danny Oberholzer went back to school at the University of Minnesota, no one knows what happened to Moose Johnson, and Chet Brewer was back with the Kansas City Monarchs. Neil Churchill had resigned his control of the Bismarck team following the 1935 season to devote more time to his car dealership--it just wasn't the same anymore!

Despite the huge losses in personnel, the team was still successful with only seven losses all season. Jamestown, unable to compete fielding an all-white team, folded during the year and were replaced by a Northern League team. The new Northern League's Jimmies won the league with a 73-50 record and had the top batter in the league, Cal Lahman, who won the league's triple crown with a .391 batting average, 48 homers and 162 RBIs. To this day, athletes attempt to match this triple crown feat by logging countless hours in the cage with quality bats

In Bismarck the stars were North Dakota veterans Axel Leary, Quincy Trouppe, Joe Desiderato, Hilton Smith and Barney Morris.

Although the season wasn't as exciting as the year before, the team still had one event to look forward to: defending their National Championship. At the urging of the Bismarck players, Neil Churchill came out of retirement, took over the team, and quickly got in touch with Major League veteran Bennie Tate, Double Duty to catch, pitch and manage, and fellow Negro Leaguers Ted Trent and Alexander Jones to bolster the pitching staff for the tournament. Satchel, however, was not available.

Despite the pitching additions, the ace of the staff was Hilton Smith, who had now blossomed into one of the most dominant pitchers in baseball. Smith, usually very reserved, boldly promised before the tournament that he would match Satchel's performance of 1935 and win four games by himself.

Honus Wagner was back in Wichita, this time as commissioner of semi-pro baseball, on a supreme court with Ty Cobb and Tris Speaker. Wagner's first act as commissioner was to call for the exclusion of integrated teams starting in 1937. All-black teams would be allowed in future years, but it would be up to each individual state to decide whether they would be allowed in state tournaments.

The 1936 Wichita National Tournament in review:

August 16, 1936: Bismarck whipped Oliver Marcelle's Denver White Elephants, 14-0, with Hilton Smith tossing a two-hit shutout. Leary, Desiderato and Harold Massmann all had a pair of hits and Double Duty led the offense with three singles, three runs, and four RBIs.

August 19, 1936: Bismarck lost its first tournament game, 8-2, when the offense and defense both fell apart. Bismarck made eight errors, and even though Ted Trent allowed only four hits, two were homers and one a triple. Morris finished the game and pitched well but Bismarck could only muster a two-run homer by Trouppe. In the seventh inning Duty caught a foul tip off the end of his index finger and broke it.

August 20, 1936: Bismarck blasted Forest City, Iowa, 7-0, on a 3-hitter by Hilton Smith. Bennie Tate doubled three times to lead the Bismarck batters.

August 21, 1936: Bismarck beat Jefferson City, Missouri, 10-0. Trent threw a three-hitter and k'd 15; Haley and Trouppe homered. In the last inning, Jefferson City sent up pinch hitter Enos Slaughter, who was promptly struck out by Trent.

August 24, 1936: Bismarck beat Flint, Michigan, 10-1, behind the pitching of Smith and the hitting of Desiderato (two hits, four runs), Massman (three hits) and Leary (two hits).

August 27, 1936: Double Duty, tired of sitting on the bench, bandaged up his broken finger and took the mound against Buford, Georgia, the only undefeated team left in the tournament. Duty pitched well, allowing three singles in 2 2/3 innings and struck out two. With the pain from his ailing digit almost unbearable, Duty took himself out of the game and Hilton Smith finished and won his fourth game of the tournament, as promised. The star slugger of the day was Desiderato who, apparently indifferent to who he was facing, collected four hits off four different pitchers--the last a double that put the game away.

August 28, 1936: Duncan, the eventual champions, eliminated Bismarck, 6-2. Bismarck had plenty chances to score--they outhit Duncan 11-7-- but hit into three double plays. Trent was anything but sharp.

Double Duty: "We couldn't get Satchel so we got Ted Trent. He got drunk the day of the last game and didn't get anybody out. I went in and stopped 'em but it was too late. They beat us and we lost the tournament. Trent was a great pitcher but he threw just like he drank--hard."

Like a meteor that burns brilliantly then disappears, so did North Dakota baseball. In 1937 Bismarck did not field a semipro baseball team. They would never field an independent semipro team again.

Downtown Bismarck ca. 1940 (ND Historical Soc.)